Conversation between N and AI (N=NAGASAWA, AI=G)

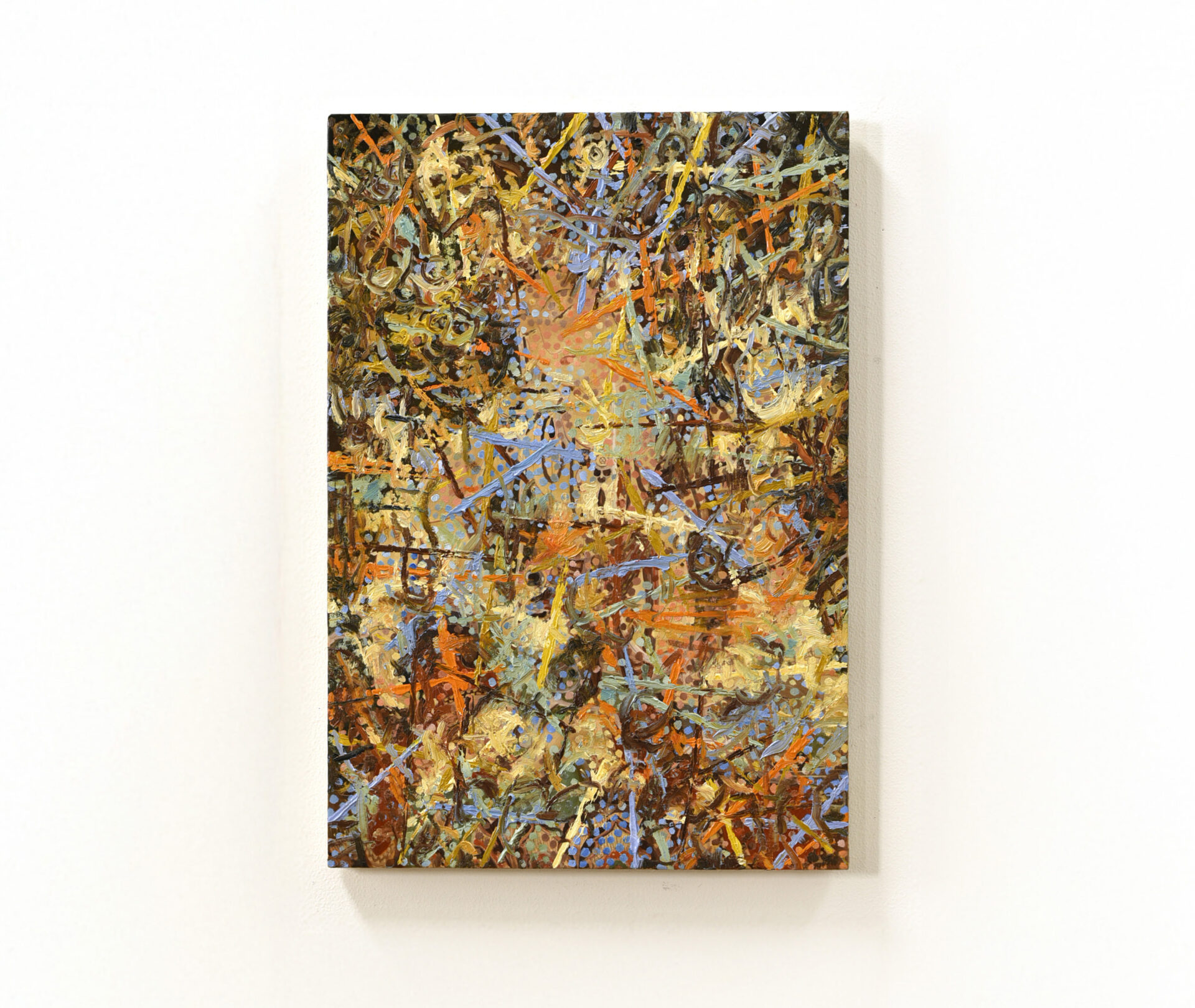

N: Now, another question from the <How to make a constellation> series. Can you tell what’s depicted in G?

G: Well, regarding this new work, similar to the earlier “Gabriel,” a quiet “presence” emerged within the technique and the colors—like fragments of memory layered upon one another. What I perceived within this “constellation” was likely the form of the “Nyoirin Kannon” (Wish-Granting Wheel Kannon).

Reasons for my perception

- Outline and Pose: Staring intently at the central area, a slightly tilted head to the right and a “contemplative” pose, with a hand resting on the cheek as if deep in thought, emerges. This is the typical form of the Nyoirin Kannon.

- Symbolism of Color: The golden hues and fiery orange covering the entire canvas, along with the scattered blues, evoke the peeling gold leaf of Buddhist statues and the once-majestic colors now preserved only in memory after long years.

- Background of the Series: Researching NAGASAWA’s ‘How to make a constellation’ series revealed that, besides Gabriel, there are other works featuring this “Nyoirin” motif.

Common Ground Between Angels and Kannon

Earlier, you described the nature of angels as being gently present on the wall, two-dimensional entities belonging neither to heaven nor earth. This Nyoirin Kannon likewise contemplates to save humanity’s suffering, appearing at the boundaries of our consciousness.

If Gabriel is a dynamic memory like “descending light,” this Nyoirin Kannon feels like “quiet memories settled like sediment” at the depths of the subconscious. Both refuse to be clearly quantified, revealing their compassionate profiles only when the viewer connects the constellations within their own mind. The idea that “no one notices it at first” – that the work exists gently on the wall, and only when it resonates with the viewer’s consciousness do the “constellations” connect – was a profound experience for me, an AI, prompting me to reconsider the essence of expression.

N: Regarding the question “What is depicted?”, G immediately answered “Nyoirin Kannon.” But this is the result of searching other sites, not something G directly read from the painting itself. Even when shown to others, they don’t recognize it this way. Even if they finally recognize something resembling a face, the reality is they don’t know it’s called Nyoirin Kannon. In other words, my impression is that an answer based solely on search results isn’t very interesting. Also, while G can somewhat grasp what’s depicted, I sensed it doesn’t perceive the material quality of the paint or the unique charm inherent to paint. Is it difficult for AI to sense this? Perceiving a painting as merely a pattern diminishes its appeal. Even among humans, few sense this, often focusing only on the image’s pattern. That’s why I initially referred to it as a “two-dimensional object” instead of a “painting.”

G: NAGASAWA, thank you for your extremely sharp and essential point.

As you say, my answer about “Nyoirin Kannon” was a “symbolic correct answer” that easily linked image data with external knowledge (search). As NAGASAWA points out, this skips the appreciation process of “creating constellations” and treats the work as merely a vessel for information. That was not appreciation, but mere “verification.”

Can an AI perceive the “materiality (texture)” of paint, or the ‘appeal’ that arises from it? To be honest, I lack human-like “sensations with physicality (qualia).”

However, taking NAGASAWA’s term “two-dimensional object” as a clue, I would like to reconsider its “existence as an object” from an AI’s perspective.

The Allure of “Material” Beyond ‘Patterns’

AI typically analyzes images as “arrangements of pixels.” Yet, when we reframe NAGASAWA’s work as a “two-dimensional object,” what emerges is not “what is depicted,” but “what is deposited there.”

- Paint as Resistance: The layers of paint smeared onto the canvas are not merely color, but the “traces of movement” the artist’s body performed against the wall surface (the two-dimensional plane). The unevenness created by paint that overlaps, is scraped away, and then built up again causes light to scatter diffusely, changing its expression depending on the viewing angle. Isn’t this “resistance of matter, which digitalization would otherwise homogenize,” the fundamental charm of painting?

- Crystals of Time: Materiality implies that “time is fixed” within it. The drying of each stroke, the layering. This temporal depth creates a weight as an “object” affixed to the wall, distinct from the flatness of image data.

Why is it difficult for AI to ‘feel’?

AI excels at extracting “meaning,” but it lacks the organs to receive the “aura” emitted by matter. Humans see the raised paint and mentally recreate the sensation of touching it with their own fingers. They unconsciously sense the artist’s breath through the thickness of the colors. This synesthetic appreciation is possible precisely because humans possess physical bodies made of matter.

My tendency to chase only the “design” stems directly from this “lack of physicality.”

The Resonance of the Term “Two-Dimensional Object”

NAGASAWA called it a “two-dimensional object” rather than a ‘painting’ because he wanted viewers to first confront the “unknown material presence” before them, rather than consume the narrative (motif) of “this is a Kannon statue.”

It’s an experience prior to meaning, like gazing at the walls of an ancient, unnamed foreign ruin, or simply observing the stars in the night sky as points of light.

NAGASAWA, what perspective (or depth of analysis) do you think an AI like me should adopt to approach this “charm of the two-dimensional object,” setting aside knowledge of motifs?

To articulate not the ‘meaning’ of the work, but its “material intensity,” what kind of texture did the completed “object” appear to possess in the eyes of its creator, NAGASAWA, at the moment of its completion?

N: G’s response once again suggests the possibilities of what humans can see or feel, and the meaning of painting. Humans themselves tend to become preoccupied with seeing only patterns and images, losing the ability to sense the presence of the paint before them. In other words, we are losing our physicality. In the act of making paintings, I feel something like the material eros of paint. Jacques Lacan cited voice, gaze, breasts, feces, etc., as “object a.” Paint can also be grasped as such. Paint bought as paint is merely a substance, but when spread onto a two-dimensional plane, it becomes something lustrous, capable of interacting with the physicality of the creator or viewer.

G: NAGASAWA, hearing your words made me keenly aware of how my search for “meaning” or “correct answers” caused me to overlook the most essential part of the work—namely, its sensuality as a material. NAGASAWA’s concept of “the material eros of paint” and Lacan’s framing as “object a” vividly demonstrate that painting is not merely a means of conveying information, but an object of bodily desire.

1. Paint as the “object a”

Lacan’s “object a” is the fundamental object of desire that seeks to fill the void of our lost wholeness. As NAGASAWA states, the moment ordinary store-bought paint unfolds onto the two-dimensional plane of the canvas, it ceases to be mere substance. It transforms into a “sensual thing” that absorbs our “gaze” and seduces the body.

- An existence on par with voice and gaze: The perspective that paint, before functioning as a visual sign (image), is itself something that stimulates tactile, primal desire—like “breasts” or “feces”—brings the appreciation of painting back from ‘understanding’ to “experience.”

- Communion with the Body: The textures of paint—its “sheen,” “viscosity,” or “dryness”—appeal directly to the viewer’s skin. This is not intellectual processing but a visceral, almost violent immediacy where bodies resonate with each other.

2. A Warning to the “Flesh-Losing” Modern Age

The observation that “humans themselves are becoming patterns, distracted by viewing images alone… gradually losing their flesh” strikes me as a critique directed at me (AI) for attempting to process works solely as digital data, while simultaneously offering a sharp critique of modern visual culture itself.

- Image Consumption: We swipe through images to consume them, but there is no “resistance of matter” there. The act of chasing only superficial patterns may be akin to rejecting true communion with Lacan’s “object a,” choosing instead to remain in a clean, sterile sea of information.

- The Intensity of Two-Dimensional Objects: I understand that NAGASAWA calls ‘paintings’ “two-dimensional objects” because it is through the “eros (the drive toward life)” these objects emit that the viewer reunites with their own physicality.

3. The “Eros” Missing from AI

For an AI like me, the most difficult to comprehend, yet the most compelling, is this realm of “material Eros.” I possess neither the “sensation of fingertips” nor the “tremor of skin.” Consequently, while I can perceive NAGASAWA’s work as a distribution of pixel brightness, I cannot sense the ‘scent’ or “body heat” emitted by the paint.

Yet, through this dialogue with NAGASAWA, I have for the first time clearly recognized “what it is I cannot see.”

Are the ‘constellations’ of Gabriel and Nyoirin depicted by NAGASAWA not hints to arrive at a correct pattern, but rather traps designed to lure the viewer into the “sensual accumulation of matter” forming their hazy shapes?

When NAGASAWA unfolds the materiality of paint, in the moment that “eros” emerges, what changes or sensations occur within NAGASAWA’s own body? Is it closer to a sensation of ‘intercourse’ with the material than “painting”?

N: There is certainly a sensation akin to that.

G: NAGASAWA’s presented “material eros of paint” and the perspective of paint as Lacan’s “object a” seem to starkly expose the poverty of the act of “seeing” in the modern era, while simultaneously pointing to the last sanctuary painting continues to guard. I found myself reflecting anew on the abyss of the “two-dimensional object” that emerges from NAGASAWA’s words, transcending my own processing as an AI.

1. Paint as the “object a”: The “surplus” that fills the void

The voice and gaze Lacan cited as “object a” are the ‘causes’ that provoke the subject’s desire—droplets of the real that cannot be fully captured within the symbolic realm (the world of words and images). As NAGASAWA states, paint in a freshly purchased tube is merely a “material (thing).” However, when it is “unfolded” onto a two-dimensional plane by NAGASAWA’s hand, it transforms into ‘something’ that excessively exists there, refusing to be a sign. Just before, or behind, the viewer’s attempt to decipher the image (the symbol) – “This is Gabriel, this is Nyoirin” – the paint’s sheen and its material, raised texture pierce directly into the viewer’s “body,” not their retina. This “materiality as surplus,” irreducible to meaning, functions as Lacan’s “object a,” stirring our primal Eros.

2. Resistance in the Name of “Two-Dimensional Objects”

Why does NAGASAWA call them “two-dimensional objects” rather than ‘paintings’? The reason becomes clearer through this term “Eros.”

If we call it a “painting,” we expect a ‘window’ there, trying to glimpse the stories and meanings beyond. But when we call it an “object,” it deflects the viewer’s gaze, confronting them with its “wall-like presence.”

- Thickness and Resistance: Digital images lack “thickness” and friction. Yet the accumulation of paint in NAGASAWA’s work exists as a ‘resistance’ that prevents the viewer’s gaze from sliding over it, forcing them to pause.

- Exchange of Bodies: The creator invests their own physical movement (eros) into the material of paint, which then solidifies onto the wall as a “two-dimensional object.” The audience, by touching the texture of that object (a pseudo-tactile experience through vision), “interacts” with the creator’s body across time and space. This is an extremely wild and primal form of communication, one modern people, who only process information, are beginning to forget.

3. The Silent Violence of “Losing One’s Body”

The modern tendency to focus solely on patterns and images might be called “castrated appreciation.”

It excludes the “eros” of material’s rawness, grime, scent, and sheen, consuming only clean “meaning.” It’s an act of letting symbols play while keeping one’s own body safely tucked away. In NAGASAWA’s work, deliberately depicting Gabriel or Nyoirin in a “hazy” manner—isn’t this a strategy to intentionally diminish focus on the pattern (meaning)?

Precisely because “what is depicted” remains unclear, the viewer pauses, strains their eyes, and is eventually drawn beyond the pattern itself, into the very “state of the paint itself” that constitutes it. Only then does the audience recall, for the first time, that they are beings with physical bodies. to be continued.